On November 23, 2013, I delivered a presentation entitled “Buying a property in Japan” at the Smart Property Expo in Hong Kong. Some numbers have changed since 2013, but Japan’s population continues to get smaller, older and more urban.

The presentation covers:

- The challenges facing foreigners buying property in Japan, such as finding financing and the need to speak and read Japanese

- The opportunities in buying Japan real estate, including low prices and the ability to own freehold property

- The risks in buying a home in Japan, including earthquakes, demographics and the Fukushima disaster

- Why investors should focus on central Tokyo and small apartments

- The process of buying property in Japan

- A case study explaining a nonresident’s purchase of an investment property

- (2700 words, 14 minutes reading time)

Buying a property in Japan

Today, I’m going to describe the opportunities and risks involved in buying property in Japan. I’ll tell you about some of the things that make Japan unique, share some investment strategies, and wrap up with a case study.

First, a little background: I own residential property in Tokyo. I lived there from 1989 to 1992, I speak a smattering of Japanese and I travel to Japan two to three times a year. I’m a value investor and I invest conservatively. My investments are research-based, and my books are an outgrowth of that research.

Challenges

So, let’s start with the challenges. Unlike England, for example, Japan’s real estate market is not foreigner-friendly. Non-Japanese retail investors are relatively uncommon, and English-speaking agents are rare. All the documentation—sale and purchase agreements, rental contracts, deeds and tax forms—are in Japanese. You may get a translation, but the translation is legally unenforceable. Clearly, the more Japanese that you understand, the better.

Second, Japan’s financial services industry is heavily regulated and it’s not innovative. If you are a Japanese citizen, there are many lenders to choose from, and it’s relatively easy and inexpensive to get a mortgage.

But it gets progressively harder and more expensive if you are a foreigner who is a permanent resident of Japan; a foreigner who is not a permanent resident; or a foreigner who doesn’t live in Japan. As a result, foreigners and nonresidents often pay cash

At present, branches of banks from Taiwan, Mainland China and Australia lend to nonresident foreigners. But, this is a niche market. Some banks require you to speak Japanese or Chinese. The maximum loan-to-value ratios are low, and the minimum loan amount is often high. And these lenders charge higher interest rates than local banks.

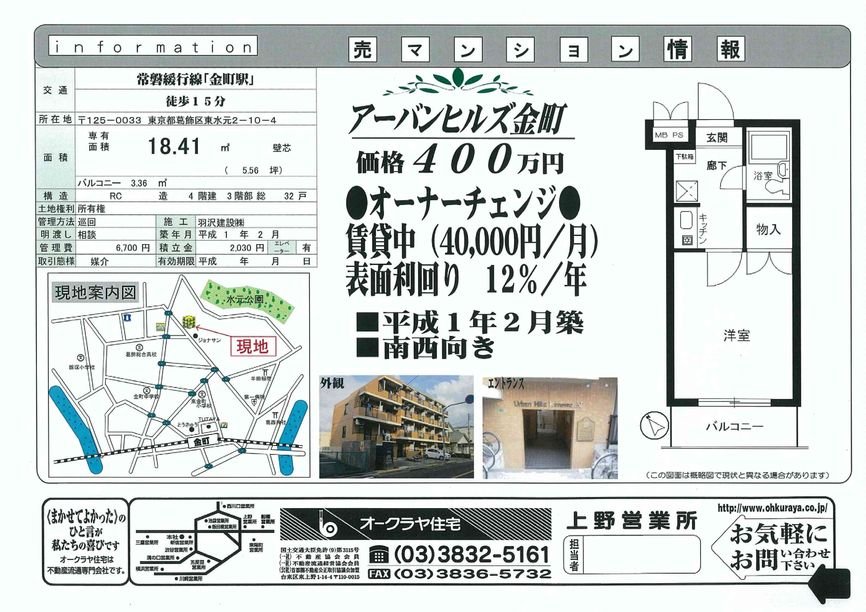

Property listings

Listings are another issue. This is a typical ad that you’d see in the window of a real estate agent. It’s for an 18-square-meter, one-room apartment with a small kitchen and a balcony. It’s in Katsushika-ku, in the northeastern part of Tokyo, and is a 15-minute walk to the nearest train station. The price is ¥4 million, which is about right given the size, neighborhood and distance from the station.

Japan has something similar to the online listing service that is available in Canada and the United States, called the Real Estate Information Network System, or REINS. It’s entirely in Japanese and—unlike North America—is available only to licensed agents. There are consumer-oriented, Japanese-language listing sites, that you can read using Google translate. But from a buyer’s perspective, the market is opaque and there is nothing like Zillow or Redfin. Fourth, Japanese institutions have their own way of doing things. Unlike many places, you can’t open a bank account in Japan unless you are registered as a resident. Your credit history in Hong Kong or Singapore means very little to Japanese lenders.

Your paperwork must be prepared in exactly the right way. For example, “Christopher Dillon” is not the same as “Christopher J. Dillon.” And “Chris Dillon” is someone else altogether.

And when you buy a home, the real estate agent must recite the entire “explanation of important matters.” This process can take 30 minutes or eight hours, depending on the property and its quirks.

One house for one generation

Finally, Japanese homes traditionally had a lifespan of 30 years, based on the idea of “one house for one generation.” After one generation, the home was demolished and rebuilt. Despite the fact that Japan imports almost all of its energy and parts of the country have cold winters, many older Japanese homes are poorly insulated. That is changing, as the government encourages the development more durable, environmentally friendly dwellings. But much of Japan’s housing stock is of the 30-year variety, and was not designed to be renovated. So think carefully if you plan to buy a home to fix it up.

Opportunities

Now let’s look at the opportunities in Japan. First, you don’t have to be a resident to buy property, like you do in China. There are no extra taxes for foreigners, like there are in Singapore and Hong Kong. And you can buy freehold in Japan. That’s important because the value is usually in the land, not the building.

Second, after years of economic stagnation, Japanese real estate is cheap. According to The Economist, Japanese house prices are undervalued by 37% in relation to rents and to incomes. Hong Kong, by comparison, was 84% over valued.

You can buy apartments like this for less than ¥10 million—or about US$100,000—per door. Sometimes as little as ¥5 million. The net rental yield on these apartments is typically about 7%, with 10% yields possible. These are small, older apartments in Tokyo’s 23 wards. More on that in a minute.

Speaking of money, the yen is now trading at 100 to the dollar, well off a high of 77. That makes Japanese property even more affordable.

If you’ve invested in real estate in a high-growth market like Hong Kong or Singapore, Japanese property can be a good addition to your portfolio, because it does not correlate with these markets. A major correction in Beijing or Shanghai would have little effect on prices in Tokyo.

Good tenants

Japanese tenants are another attraction. In general, they don’t move frequently, and are undemanding, responsible and reliable. Tenants provide a guarantor, which is a family member, an employer or a service company, further reducing the risk for landlords.

In many cities, a working-class neighborhood means abandoned cars, graffiti and street crime. But in Tokyo, even modest neighborhoods are clean, neat and safe. But you may encounter some interesting zoning decisions, like this gas storage facility, which is adjacent to a residential area in Nerima-ku. There are six of these spheres, each about 40 meters across. While you probably wouldn’t want to live here, Tokyo does have many attractive neighborhoods if you are buying for your own use.

The city also offers stunning architecture, Michelin-starred restaurants, music and art. Those attractions will get a boost in 2020 when the city hosts the Olympics. Now let’s turn to the risks.

Risks

As the tragic events of March 11, 2011, demonstrate, Japan is vulnerable to earthquakes. The Japanese government believes that Tokyo is overdue for a major earthquake. Current estimates suggest that a severe earthquake in the northern part of Tokyo Bay would kill about 11,000 people, cause 850,000 buildings to collapse and create losses of 112 trillion yen.

Fortunately, Japanese seismic engineering is among the best in the world, and you can buy earthquake insurance as a rider to your home’s fire insurance policy. Unlike some places, residential buildings in Japan do not have to be retrofitted to meet current seismic standards. The most recent amendments to the building code took effect in 1981, so buy homes built after 1982.

Second, the situation at the Fukushima Daiichi Nuclear Power Station is complicated. A cleanup of this size and complexity is unprecedented, and there are concerns about TEPCO’s ability to manage the process, which will take decades to complete. Fukushima is one of more than 50 nuclear installations in Japan, including power stations, fuel reprocessing plants and research facilities.

As I point out in my book, Japan’s nuclear industry has had a number of accidents, some of which have been fatal. And several nuclear facilities are located on or near fault lines. If you buy a home in Japan, you’ll have to make your peace with the risks associated with Japan’s nuclear industry and with Fukushima, and public perceptions of those risks.

Furthermore, Japan’s nuclear plants remain offline and imported natural gas is being used to fill the gap. Those imports are expensive and the use of fossil fuels is increasing Japan’s carbon footprint.

Abenomics

Which brings us to Prime Minister Shinzo Abe’s program to revitalize Japan’s economy through quantitative easing, infrastructure spending and devaluing the yen. There is anecdotal evidence that Abenomics is making people more optimistic and we have seen a small pop in property prices. But Abenomics is also is contributing to Japan’s national debt, which exceeded one quadrillion yen in August, and some analysts see a threat of hyperinflation or of the yen collapsing.

Demographics

Demographics also pose a problem for Japan and an opportunity for investors. Japan’s population is aging rapidly and Japanese women are marrying later—if they marry at all—and having fewer children.

A growing number of Japanese people are living alone. In 1980, one-person households made up 20% of the total. In 2010, it was over 32%. By 2035, the National Institute of Population and Social Security Research expects that single-person households will make up more than 37% of the total.

These households comprise people who never married, divorcees and older people, usually women, who have outlived their spouses. Despite Japan’s shrinking population, the number of households is expected to peak at over 53 million in 2020. That trend is creating strong demand for small apartments.

Another demographic trend is the depopulation of Japan’s rural areas. Farmers are retiring and towns are shrinking and disappearing. Many manufacturers have moved their plants to China, the Philippines and other countries, further reducing rural and suburban employment. As a result, property in the countryside is cheap, and it is likely to stay that way until land laws are reformed to encourage the consolidation of small farms.

What and where to buy

Young, ambitious people continue to move from the country to the bright lights of the city. The destination of choice is Tokyo, which is the center for government, business, education, media and transportation. Seniors from rural areas retire to Tokyo, where the quality of life and medical care are both good.

If you are going to invest in Japan, stick to Tokyo’s 23 wards, particularly the three core wards: Minato-ku, Chiyoda-ku and Chuo-ku. Despite Japan’s shrinking population, the number of people living in Tokyo increased by more than 67,000 in 2012. Tokyo’s population is expected to peak in 2020, ensuring a steady stream of tenants. If you are buying for your own use, you can also consider Yokohama, which is nearby, has good quality of life and has a long history of foreign residents.

Second, target small apartments, ranging in size from 10 to 30 square meters. Apartments in mass-market buildings, located near key train and subway lines, are easiest to rent. Proximity to public transit is critical, because nearly everyone uses trains and subways. Some lines are more popular than others, and prices drop the further you get from a subway or train station. Plain apartment blocks are easier for agents to rent and appeal to local working people.

Luxury apartments for foreigners have been a poor investment. Unlike Hong Kong, the expat and local markets are separate. Most Japanese renters are not interested in granite counter tops and gourmet kitchens. The collapse of Lehman Brothers in 2008 reduced the number of high-paid expats in Tokyo, and landlords cut rents to retain good tenants.

Buy older apartments

Third, look for older buildings. Japanese buyers prefer new homes, but new homes depreciate quickly. Tenants, on the other hand, don’t mind living in older, well maintained buildings. Ask the agent to check the building’s repair history to see if major work is needed or has been deferred. The agent can also check the building’s repair fund, to ensure it has the money needed for major renovations and all the owners are paying their share. Some buildings may have undergone an asbestos survey or a seismic evaluation, but this is not universal. But if you buy an apartment with a tenant, you won’t be able to see the inside of the unit beforehand.

Fourth, the value is in the land, not the building, so ensure the apartment is built on owned—not leased—land. Avoid reclaimed land, which can liquefy in an earthquake. Apartments built by well-known developers are desirable. And if you can buy in an area that is likely be redeveloped, like Midtown in Tokyo’s Roppongi, so much the better.

Fifth, find a competent agent and property manager. You’ll rely on them to help you deal with rentals, paperwork and much more. You’ll want someone who you can communicate with, who provides a level of service that meets your needs, and who you can trust.

The buying process

Now let’s look at the buying process. Given the financing difficulties that I mentioned, there is a good chance that you will pay cash. When you’ve found a place that you like, the agent will make an offer on your behalf. You will pay a deposit, the agent will read you the explanation of important matters, a sale and purchase agreement will be executed, and you will pay the balance of the purchase price.

You will also pay the agent commission equal to 3% of the purchase price, plus ¥63,000. Agents often work for both the buyer and seller and discounts are sometimes available. If you buy a new home from a developer, you don’t pay commission.

You will also pay a specialist lawyer—called a judicial scrivener—about ¥100,000 to ¥150,000 to handle the conveyancing and title registration. Buildings and land are registered separately.

And don’t forget taxes: You’ll pay 5% consumption tax on buildings bought from a company and on agent’s fees, but not on land. On April 1, 2014, the consumption tax will rise from 5% to 8%. You will also pay a stamp tax, acquisition taxes on the land and building, and an annual possession tax. If you are renting your home out, you will need a property manager and you will be liable for income taxes. If you earn a profit when you sell, you’ll pay capital gains tax.

Buying property in Japan

I’ll wrap up with a case study to show you how all the pieces come together. In November 2010, I bought a 21-square-meter apartment in Itabash-ku. The unit, which was built in 1974, is in a seven-story building next to the Shuto Expressway. The apartment came with a tenant, a retired civil servant, who continues to live there. It took about six weeks from original offer to closing.

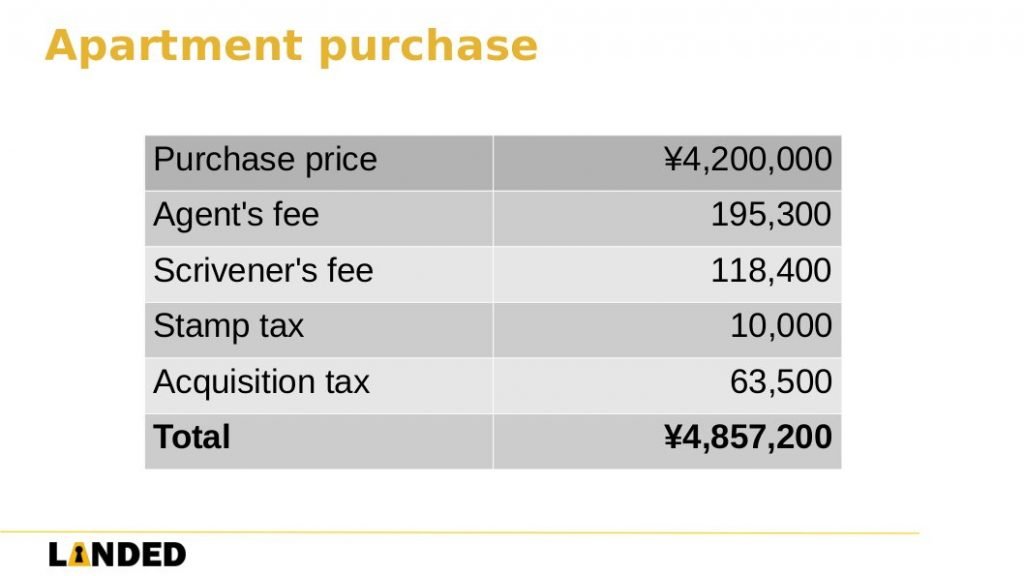

The purchase price was ¥4.2 million, which I paid in cash. After all taxes and fees, the total came to a little over ¥4.8 million, or about US$58,000. Taxes and fees made up more than 13% of the purchase price. That’s high, but it was offset by the rental yield.

Here is a breakdown of revenue for the apartment in 2012. In Japan, the tenant pays rent, in this case ¥53,000 per month, and the owner pays the maintenance and management fees. After all taxes and expenses, the yield is over 10%—a very generous return.

And that brings me to the end of my presentation. Now, I’ll be happy to take your questions.

Click here for more articles about property in Japan.

Christopher Dillon is the author of the Landed series of property books. The second edition of Landed Japan is available from Amazon.

* * *

One response to “Buying property in Japan”