Updated March 12, 2025—Scuba diving in Hong Kong, you’ll see numerous nudibranches, poisonous pufferfish and the odd octopus. On September 14, 2024, my buddy Edmund Lee and I spotted something different, a submerged UXO (unexploded ordnance), that turned out to be a World War II bomb.

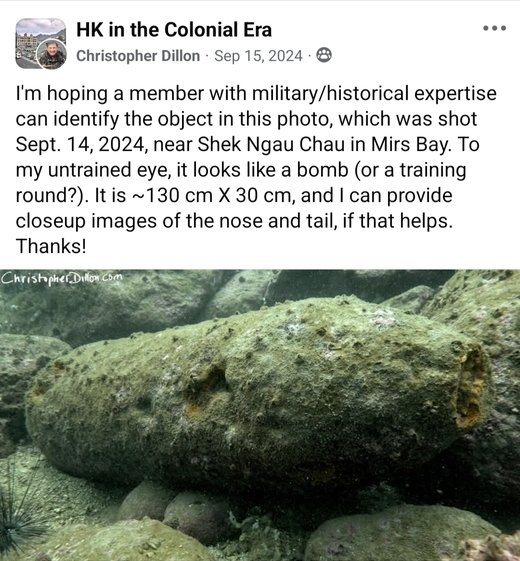

At lunchtime the next day, I posted a photo of our discovery on the Facebook group “HK in the Colonial Era.” This group is popular with amateur historians and military history buffs, and I hoped someone could determine if the device was a UXO, a practice bomb or something else.

Within minutes, a group member asked if I had reported the device to the authorities. When I told him I hadn’t, he offered to introduce me to the Hong Kong Police’s Explosive Ordnance Disposal (EOD) Bureau. Less than 30 minutes after posting the photo, an EOD officer contacted me, asking for more information.

At this point, I didn’t know what to expect. Would the police care about what “could” be a bomb, in a remote part of the territory, under 40 feet of seawater? And if they were interested, then what?

The submerged UXO’s location, near Shek Ngau Chau in Mirs Bay

Questions, questions

Over the next week, I answered questions about the suspected bomb and its location, on the east side of Shek Ngau Chau, an island in Mirs Bay. I also shared photos of the device with the EOD officer, who said it could be an AN-M64, a 500-pound (227 kilogram) aerial bomb manufactured in the United States starting in 1943.

That seemed to describe the object we discovered. The AN-M64 was 57 inches (145 centimeters) long, 14 inches in diameter and contained up to 267 pounds of TNT. On land, it could produce a blast radius of more than 1,500 meters. And, according to the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, TNT is poisonous and a potential human carcinogen.

People have asked how I spotted the bomb. The answer has three parts. The first is luck: looking in the right place at the right time. Second, while diving I watch for motion and unusual colors and shapes, which often suggest a photo opportunity. Finally, the submerged UXO was big, and its profile included circles and ruler-straight lines, which are rare in nature.

I’ve also been asked if I handled the device. I’m from the “look but don’t touch” school of diving, so handling the submerged UXO never entered my mind.

On September 21, the EOD officer asked if I could join a team of police divers in a search operation. I immediately agreed. But this presented a new question: Could I find the bomb again?

Locating the submerged UXO

Visibility varies in Hong Kong waters. On a good day, 10 meters is possible. But 50 centimeters is not unusual. After some eight decades, the suspected bomb was camouflaged with layers of marine life. It was also sitting at 13 meters, where less than 16% of the sunlight falling on the ocean’s surface penetrates. At depth, sunlight is diffuse and long-wavelength colors—like red, orange and yellow—are attenuated. The lack of light, contrast and color, as well as the ocean’s sheer size, makes underwater searches difficult.

Despite these challenges, I was confident. But I didn’t want to waste the EOD Bureau’s time.

Over the past decade, I’ve made about 300 dives in Hong Kong waters with the South China Diving Club. Some dive sites—like the Dolosse on the High Island Reservoir—are instantly recognizable. Others, such as the artificial reefs in the Hoi Ha Wan Marine Park, have no surface marker. And there are many large sites, like Basalt Island, where multiple dive plans are possible. As a result, I often use my phone’s GPS app to track dives and a Nikon DSLR to capture scenery above the waterline.

Gathering data

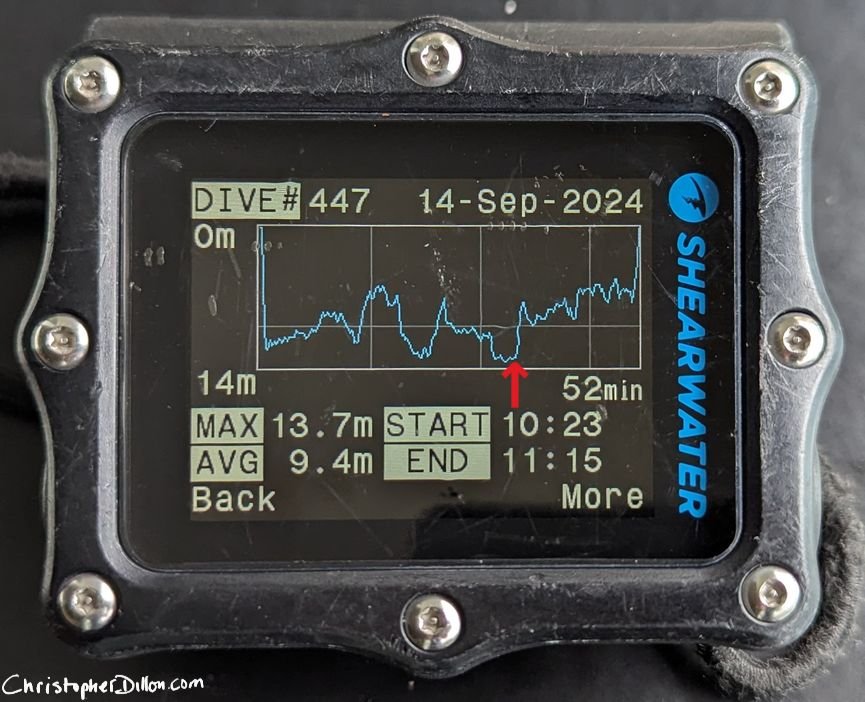

On the September 14 dive, I took a GPS reading and surface photos, and photographed the suspected bomb with my underwater camera, an Olympus TG-5. The images were timestamped, and my dive computer showed when I submerged and surfaced, as well as my depth throughout the dive.

With this data, I determined the dive’s approximate starting point and direction; confirmed the co-ordinates with landmarks on the surface; and estimated the submerged UXO’s location and depth. That seemed like a good start.

Diving with the police

On the morning of September 23, the EOD team picked me and 25 kilograms of equipment up from my home on Hong Kong Island and drove me to Hung Hom to meet the police divers. For operational security reasons, photography and video were forbidden.

Being a diver spans a range of skill levels. There are hobbyists who dive twice a year on sun-dappled tropical reefs, as well as professionals who work in deep, dark, near-freezing water. There is a similarly broad spectrum of qualifications, covering everything from basic scuba skills to the exotic breathing-gas mixtures used in technical diving. So I wasn’t surprised when I was asked to show my certification cards and quizzed about my experience. As the police divers explained, they were responsible for my safety, and their own.

With formalities completed, we drove to the Marine North Division Police Station at Ma Liu Shui, and took a police boat to Mirs Bay. Then we transferred to a smaller launch, which was our dive platform for the search.

The search begins

The police planned two dives, each with a maximum bottom time of one hour. Our first dive lasted 16 minutes. We surfaced for two minutes, so the divers could confer with the officer on the launch who was managing the operation, and submerged again to resume the search.

Ten minutes later, we found the bomb. After fist bumps, the police divers attached a delayed surface marker buoy (DSMB) to a reel and lead weight, and positioned it near the device. The inflated DSMB shot to the surface, indicating the bomb’s location.

The police divers and I climbed aboard the launch and made way for a team of EOD divers, who conducted a detailed investigation of the device. The EOD Bureau confirmed we had discovered a bomb and recorded its location. They also made plans to detonate the submerged UXO when the area was clear of people, and the tides and weather conditions were suitable.

On the afternoon of October 8, the police destroyed the submerged UXO, which they identified as a 500-pound Japanese aerial bomb from World War II, using a controlled explosion.

Update

On March 6, 2025, the South China Diving club hosted an informative presentation by the EOD Bureau.

The presentation covered the locations and types of explosive devices found in Hong Kong, and information about how these devices are disabled.

If divers find a suspected explosive device in Hong Kong waters, they should note the depth and location, and make an e-report or call to the police hotline (2527 7177). The EOD Bureau is on standby 24/7. and will follow up on your report.

Anyone finding a suspected explosive device on land—where it could pose a threat to people and property—can report it by telephone to the police emergency hotline (999).

UXO in Hong Kong

It’s been nearly 80 years since the end of the Second World War, but unexploded ordnance is still being discovered in Hong Kong.

During the Japanese occupation (December 25, 1941–August 15, 1945), American aviators dropped thousands of bombs on Hong Kong. In a single eight-hour raid on January 16, 1945, nearly 500 aircraft dropped 154 tonnes of ordnance on Japanese ships, as well as docks and refineries, mainly around Victoria Harbor.

Today, UXO are discovered during the excavation of building foundations and civil engineering projects. Weighing as much as 2,000 pounds, the bombs become increasingly unstable as they age.

My first encounter with UXO in Hong Kong was on March 17, 2000, when my taxi was diverted around an operation to defuse a 500-pound bomb that was discovered during the construction of a bypass near Queen Mary Hospital in Pokfulam.

After evacuating the hospital, the EOD squad burned off as much of the explosive as possible. At 4:30 AM, they conducted a controlled explosion with the remaining material, resulting in a small fire on a nearby hillside. Television news coverage of the operation is available here.

Christopher Dillon chaired the Hong Kong–based South China Diving Club from 2018 to 2020.

This post was originally published on October 13, 2024.

* * *