Turning old factories into homes is a common redevelopment strategy in many big cities. Christopher Dillon looks at why loft conversions haven’t taken off in Hong Kong.

A major manufacturing center

If you’re under 30 or new to Hong Kong, you may not know that our city was once a major manufacturing center. Hong Kong’s low labor costs, central location and deep harbor made it a natural place to produce clothes, toys and a range of other goods. A visit to the Hong Kong Museum of History quickly confirms how important light manufacturing was to our economy from the end of World War II until the 1970s.

But as wages rose, the price of local real estate increased and China started welcoming foreign factories, Hong Kong’s appeal as a manufacturing base began to decline. Today, manufacturing plays a relatively minor role in our economy. But at the end of 2005, Hong Kong had more than 17 million square meters of factory space, of which more than 1.2 million square meters were vacant

Loft conversions overseas

In the Americas, Europe and Australia, large cities faced similar challenges when manufacturers left inner city neighborhoods in search of less expensive labor in developing economies and cheaper, more modern space in industrial parks. Factories would be abandoned or sit vacant until artists, students and other pioneers began to move in, often illegally. The new residents of these “loft” apartments lent these neighborhoods a sense of flair and excitement. In time, investors and speculators began buying the factories, and areas such as New York’s SoHo, Flatiron and Tribeca were revitalized.

The original loft-dwellers were motivated by a desire for cheap, plentiful space. As industrial neighborhoods were renewed, they were displaced by wealthy professionals who also wanted space and a central location. Both the pioneers and the yuppies liked the idea of an alternative lifestyle and escaping the blandness of the suburbs.

Why not Hong Kong?

With their large, open spaces and abundant natural light, lofts are now found in many cosmopolitan cities. So why don’t we have them in Hong Kong?

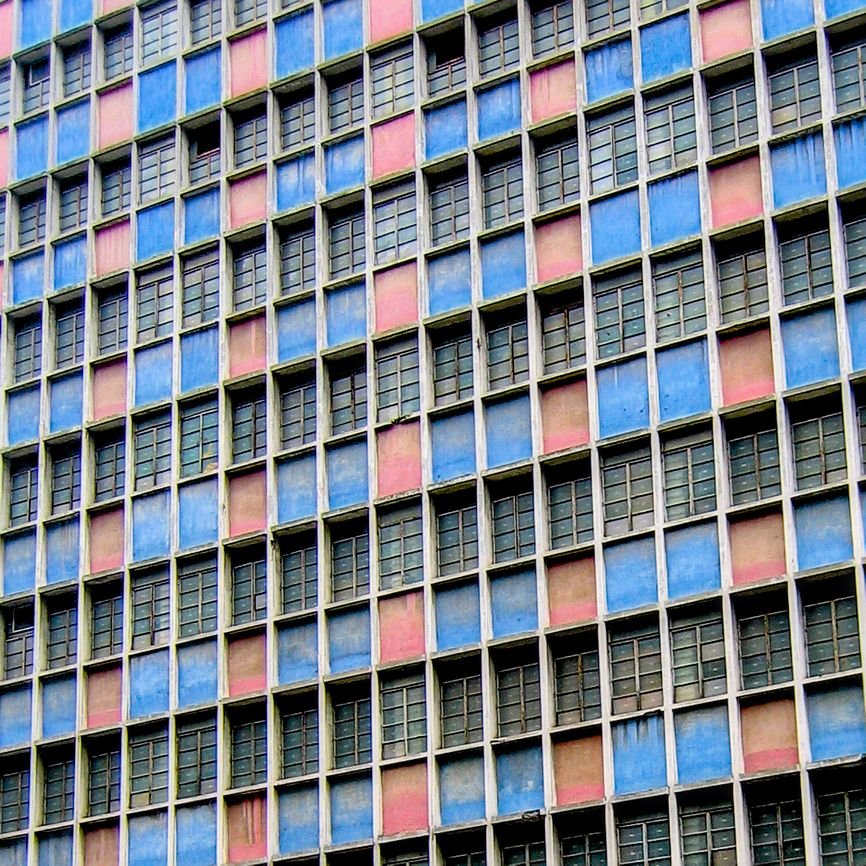

One reason is architecture. Overseas, lofts are often located in 50- to 100-year-old buildings with high ceilings, exposed brick walls, hardwood floors and large windows. With money and imagination, these buildings can be transformed into unique, visually interesting homes, offices and boutiques. By contrast, more than 90% of Hong Kong’s factories were built after 1970. Concrete boxes are the norm, and there aren’t many architectural details to give these buildings character.

Financing is another issue. On an indexed basis, where 1999 equals 100, the value of factory space plummeted from 171.4 in 1996 to 71.7 in 2003. By the end of 2005, values had rebounded to 135.9, well below peak prices. This volatility left lenders gun-shy. An informal survey in 2005 found firms that were willing to provide a factory mortgage used valuations that were five to 40% below market, would lend 50 to 60% of that value, and wanted a one-percentage-point premium over the prime lending rate. Mortgage terms like these make conventional flats much more attractive.

Hong Kong people also value conformity. Ease of resale and financing make a 400-square-foot flat in Sha Tin more desirable than something as unconventional as a remodeled walk-up in Soho. For most people, the idea of living in a converted factory is simply beyond imagining.

Regulatory hurdles

Regulations governing local property are perhaps the biggest obstacle. As part of “Hong Kong 2030,” a strategic plan for the territory’s physical development, the Hong Kong Government commissioned a number of working papers, including one that examined the feasibility of converting selected industrial buildings in Ma Tau Kok and Yau Tong into lofts.

Despite these challenges, the paper concluded that loft conversions could be viable in Hong Kong, but only if developers were not charged a premium for changing the building from industrial to residential use. The authors recommended that government consider changes to the premium policy to facilitate loft conversions. However, the Planning Department said that no progress had been made since the working paper was published in September 2002.

The working paper assumed the loft conversions would occur on a whole-building basis, which would limit participation to large developers and exclude the smaller companies and individuals who usually pioneer these developments. It also specified that the factory buildings’ plot ratio (the net floor area divided by the net site area) would need to be reduced to meet the regulations for residential buildings, a condition that would require considerable amounts of demolition and negate the point of the conversions. One of the working paper’s conceptual plans even included a clubhouse, something that is common in Hong Kong apartment blocks, but that would be decidedly out of place in most lofts.

So, if it is impossible to legally convert a factory into a loft, what are the alternatives?

Risk factors

According to the Buildings Department, living in an industrial space would qualify as “unauthorized building works” and result in a maximum fine of HK$200,000 (US$25,600), additional fines of up to $20,000 for each subsequent day that the tenant failed to comply with an order to vacate the premises, and a maximum of one year in jail.

If this doesn’t deter you, there are landlords in Hong Kong who will happily look the other way. Mr. J, who has lived with his wife in a 2,000-square-foot industrial space on Hong Kong Island for the past two years, loves it. “The main attraction is the dollar-per-square foot ratio. You save a lot of money, and it’s contrarian—when we’re home, the other residents aren’t. About the only downside is that occasionally you’ll hear industrial machinery at night.”

Aside from noise and surprise inspections by the Lands, Buildings and Fire departments, there are some other disadvantages. There is the risk of contamination by previous tenants, who may have used noxious chemicals. Many factory buildings have been neglected and leak when it rains. You could end up with a metal-stamping plant next door.

Economic incentives

However, low prices (and the ability to throw loud parties) can be a powerful incentive. Currently, rent for factory space in Aberdeen starts at $5 per square foot, while units can be purchased for less than $1,000 per square foot. That is substantially less than the $3,000-plus per square foot to buy residential property in Aberdeen, or $12,000-plus for a flat in nearby Shouson Hill.

While it is unlikely that Hong Kong will embrace loft living with the enthusiasm found in London, the Planning Department says it will address the conversion issue again in a round of public consultations scheduled for the first half of 2007. And it’s possible that the combination of rising real estate prices and renewed interest in preserving Hong Kong’s heritage may give this movement the boost that it needs.

Click here for more articles about property in Hong Kong.

The second edition of Landed Hong Kong is available from Amazon.com.

This story first appeared in the January 2007 edition of The Correspondent, the official publication of the Foreign Correspondents’ Club in Hong Kong.

* * *