December 13, 2024—This post describes the creation of a family photo archive hosted on Permanent.org.

The photo archive comprises nearly 1,600 files. It includes shots from a copy stand, scans of 35mm negatives and slides, native digital images, video and documents. Images were processed with the open source program darktable and renamed with digiKam, running on POP!_OS 22.04 (Linux).

Contents

Why create a family photo archive?

Source materials

Subjects for the photo archive

Curation

Time and emotion

Dating the images

Tagging the images

Using Permanent.org as a photo archive

Why create a family photo archive?

I built the archive because my family has lived in three countries. We’ve travelled extensively, and experienced historic events, such as Hong Kong’s return to China. The archive let me organize and make those memories accessible to current and future generations.

I also hoped to give my adult third-culture kids a sense of their origins, and share our adventures with distant relatives. Finally, the photo archive was a learning opportunity, and a handcrafted Christmas gift for my family.

Source materials

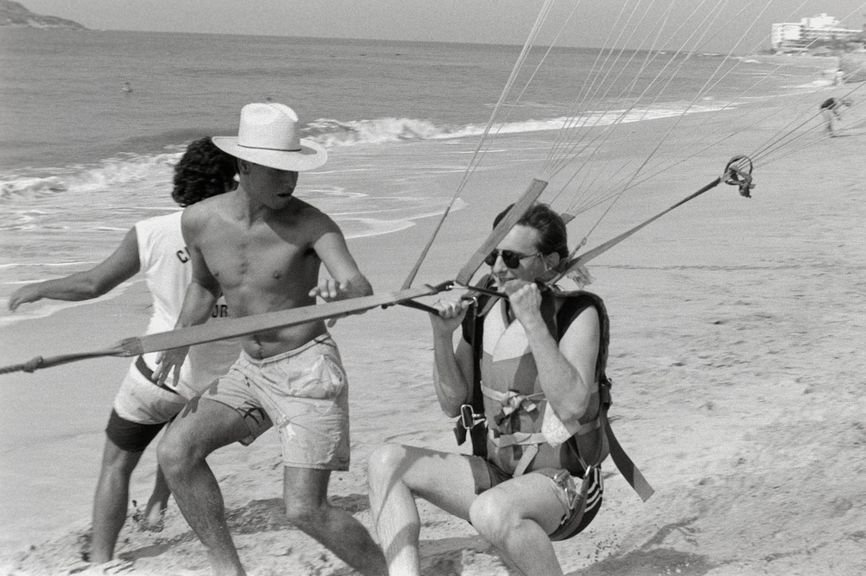

Loose prints: Old B&W shots from my mother; images from friends, schools, charities and clients; and Polaroids and photo booth output. These were digitized on a homemade copy stand with a Nikon D810.

35mm slides and negatives: Shot between about 1980 and 2000, these were digitized using a BlackBox 135 scanner and the D810.

Digital images: These were shot on Canon point-and-shoot cameras from the early 2000s, and Nikon DX and full-frame DSLRs. Friends and family donated files, some shot on mobile phones.

Documents: Diplomas, certificates, newspaper and magazine clippings, event programs, tickets and correspondence. These were digitized with the copy stand or a Brother DS-640 document scanner and Xsane 0.999 software.

Video: Segments from CNN, Bloomberg and local TV, plus client and personal projects.

Subjects for the photo archive

People comprise the overwhelming majority of the images in the collection. Immediate and extended family are the core subjects, supplemented by friends, coaches and teammates, teachers and classmates, coworkers and fellow club members.

There’s an emphasis on action—people singing, dancing, working, playing rugby, scuba diving, making presentations and participating in charity events. There are a few posed images, like graduation photos.

The archive includes people outside these categories. But they are part of shared experiences, like musicians at concerts we attended and the protests that rocked Hong Kong in 2019.

There are images of things in the collection, like my kids’ rugby awards and my grandfather’s passport. These objects mark milestones or provide insights into our family. And there are random items, like invitations and backstage passes, that might spark a memory or conversation.

Curation

I had about 30,000 images to choose from. That made curation both difficult and essential. Deleting duplicates and culling flawed images (while keeping and tweaking imperfect-but-meaningful ones), was time-consuming but made the collection more coherent.

I excluded unflattering images. Using darktable’s censorize function, I redacted sensitive information, such as birthdates, on documents.

Aesthetically interesting images (like my undersea and street photography) that didn’t advance the family-centered theme were also cut. Less really is more.

This started as a project to digitize about 180 rolls of 35mm negatives and slides. As the project became a photo archive, I found Adam Pratt’s book Declutter Your Photo Life to be a helpful resource.

Time and emotion

Creating a family photo archive is an intensely personal process. It’s easy to get sidetracked by images of old family vacations or long-dead relatives. The archive was a labor of love. And it took longer than expected.

It’s discouraging when you find negatives from a memorable event that were ruined by poor storage. And that feeling grows after your third consecutive unusable roll. But this was offset by the discovery of long-forgotten happy memories.

I started by scanning film images as I found them. Then, I used digiKam to rename the files using this pattern: “year-month-day – short description – image number.extension”. This created a major “aha!” moment when the files sorted themselves by date. Suddenly, a pile of random images had structure. I could see my kids grow from toddlers to teenagers, and the archive began to take shape.

Only minor adjustments—mainly cropping, exposure and contrast—were made to the scanned images. Given the number of files, anything more would have been impractical.

Images were uploaded to Permanent.org as JPEGs output at darktable’s 90% quality setting. I used a fixed width of 1,800 pixels and variable height.

About 20% of the archive is from the analog era. Preserving, organizing and tagging that material was especially important. So many unlabeled snapshots—and the memories they contain—end up in a landfill.

Dating the images

Assigning dates to the slides, negatives and loose prints was an inexact process. I made a first pass using photo lab packaging, dates on the borders of old B&W prints and clues from the images themselves.

I wrote a chronology of key life events, travel and places I’ve lived, using passports, utility bills and other documents. Recurring events, like birthdays, vacations and Christmas, provided additional references. When I didn’t know the month or day, I used “00”.

Then made a second pass, using nearby images for context. As I added items to the archive, I fixed misdated files. I’m sure mistakes remain, but to paraphrase General George S. Patton:

“A good family photo archive violently executed now is better than a perfect one executed at some indefinite time in the future.”

Tagging the images

I added a description to images I scanned or shot on the copy stand using darktable’s metadata editor. I did the same with native digital images. The descriptions range from simple, like “Alexander playing rugby,” to 100-word mini-essays. This text was copied to the description section of each image’s Permanent.org entry.

Permanent.org lets you add keywords—which I only used to tag family members—to each file. Because keywords are selected from a list, this approach ensures people are identified consistently (“Al” vs. “Alex” vs. “Alexander”) and names are spelled correctly. A text expander saved many keystrokes when writing descriptions.

I standardized the names of people who have been married or divorced. I have one relative who married, divorced and remarried. She is tagged: “first name (maiden name / first married-name) current married-name.” Be careful not to deadname anyone.

Using Permanent.org as a photo archive

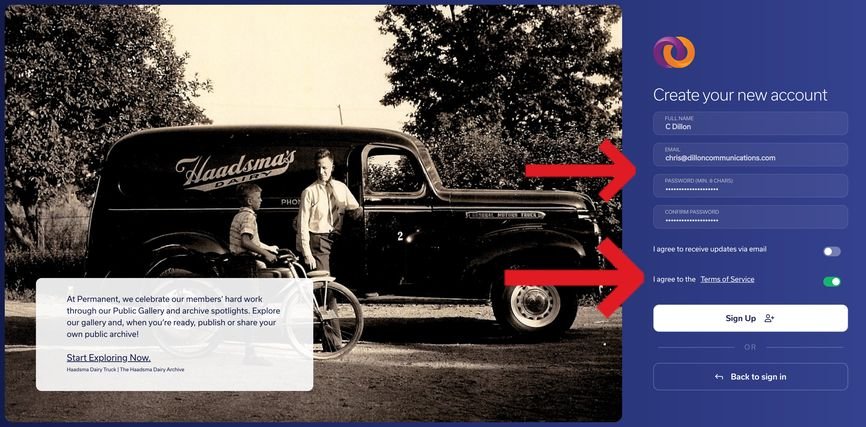

I chose Permanent.org over Google Photos, Flickr, Smugmug, etc., because it’s a 501(c) registered charity in the United States. It is funded by an endowment, so you pay once for permanent storage, which will allow my images to be shared with the next generation. Permanent.org is designed for family archives, has mobile apps, and they don’t harvest your data like Google does.

That said, you need a free account to see full-size images and read the images’ descriptions. When the archive began to take shape, I asked a friend and fellow photographer to beta test it. Her feedback revealed the signup and archive access processes were more complicated than when I joined several years ago. So I created a detailed guide for my less technically inclined family members.

Permanent.org doesn’t have a slideshow function, or the most intuitive interface. But it handles JPEGs, PDFs and MP4s natively, and lets registered users download files.

Permanent.org lets you search images by keyword, and by the text in the description and the file and folder names. There is an extensive knowledge base, and it has many thoughtful features, like the ability to appoint a successor to manage the account when you die.

You can also manage access to your archives. For now, mine will only be available to immediate family, but there are sample public archives on the Permanent.org website.

Ultimately, I was won over by Permanent.org’s value for money and its commitment to long-term preservation.

Christopher Dillon is a Hong Kong–based writer, photographer and entrepreneur.

* * *